James Webster: Did Guernsey's 'strangest election in the world' live up to the name?

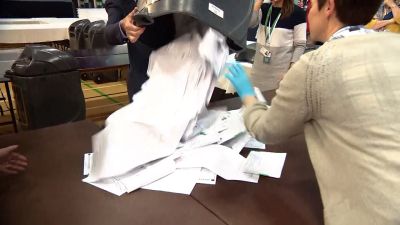

The trestle tables have been folded up, the ballot papers are packed away and the counting machines have done their job. Guernsey's General Election has produced 38 new Deputies to take their seats in the States Assembly. So often we have been reminded that this is the first time that has happened on an 'island-wide' basis, so what have we learnt through the process? To people living outside of Guernsey the very spectacle of a ballot paper containing 119 names with each voter able to cast as many as 38 votes raised eyebrows. The Electoral Reform Society questioned whether it was "the strangest election in the world" that would be "difficult and overwhelming" for voters. It seemed eccentric at best and some questioned the wisdom of such a complex system for such a small electorate. For us as journalists, general elections are exciting times. They are opportunities to question those in power, speak to voters about the issues they consider most important as we follow the twists and turns of the campaigns before polling starts. Then there's the excitement of the results and seeing what has changed since the last election. But (and here's another phrase we heard all too often) this was an election like no other. Not just in Guernsey was it unique but experts told us they didn't know of anywhere else in the world that has run an election in a comparable way. Predictions were impossible. How many votes would be cast? Would there be clear results? How long would the counting take? So many unknowns. Our biggest challenge in the weeks running up to the election was how we could cover the campaign on our programme and online. Usually you would be able to produce reports about the different districts, speaking to candidates and people living in those parishes. Not this time. With just one constituency and a responsibility to be fair to all candidates it was impossible for us to give balance to all those who were standing if we started interviewing them. Our only choice was to not interview any candidates.

It felt strange covering an election where the electorate want and need to hear from the candidates and they were the very people who were entirely absent from the coverage. We could discuss issues, interview voters about their priorities, see carefully chosen shots of hustings events that didn't favour particular candidates, but we could not hear from them at all. We worried whether our viewers would be sitting at home asking why we weren't speaking to any candidates. Would people understand why we weren't interviewing candidates? Would they feel we were doing them a disservice? Just another one of the big unknowns for us during the weeks of the campaign. In the end, I think our coverage was interesting, it provoked debate, it reflected the campaign, but it reflected the fact that this was a campaign that put more responsibility on voters to engage in the process themselves.

Voters would have to do their own research into who they would choose. The hefty book of manifestos and the online profiles of each candidate, coupled with the hustings events, were all they had to make up their mind who would get their vote. And it relied on them making the time to do so. Having covered many elections before in the UK I can't help feeling that many people go to the ballot box without ever having read a manifesto. In Guernsey this was exactly what people were being told to do - 119 times.

As we approached results day we knew that we wanted to be able to analyse the votes quickly and see how people had voted, to identify patterns and changes and understand what this meant for the new States Assembly.

We created a spreadsheet to analyse the results and compare them to the previous election results. If the States had brought in a counting machine to tot up the potential 1 million or more votes, we needed more than just pen and paper. It was hard to know which statistics would even be interesting. Comparisons of vote numbers with 2016 were meaningless but percentage changes could tell us more of the story.

We wanted to see how the make-up of the States varied by geography, diversity, political party, and their opinion on controversial education reforms.

Come the results declaration (and the recount on Sunday) and the spreadsheet spat out its analysis. It told us more quickly than the officer declaring the results not just which politicians had been elected, but which ones had been kicked out. Those were the headline points but there were other details we could very quickly see too:

There was a clear majority in the new States for some form of three school secondary education model .

Now we can look back at the election, I find the raised eyebrows over the new electoral system unfair. It has to be remembered that this was a system chosen by a referendum. In 2018 45% of people turned out to vote in a referendum and more than half of them chose to change to island-wide voting. This was a system the island wanted and what the election shows is that the electorate overwhelmingly embraced it and made the most of their new votes.

A turnout of almost 80% was a significant increase from 2016 and with each voter using on average 26 of their 38 votes, it seemed like people had taken the time to consider all the candidates and choose an extensive list of the politicians they wanted to represent them for the next political term. It has been a fascinating few weeks watching the election unfold, but like any election this is not the end of the story. This is just the beginning of a new story which will unfold as Guernsey's new politicians take their seats this week and begin making their mark on the island's politics.