Children in Crisis: Are we failing young minds?

A special investigation into whether services for children with mental health problems are fit for purpose.

By Yasmin Bodalbhai, ITV News Central

It started with a simple social media post.

When we first asked viewers to share their experiences of child mental health provision, we knew we would get some response - we’d been hearing anecdotally about parents struggling to get help for their child’s mental health problems. But we weren’t prepared for the avalanche of comments and emails.

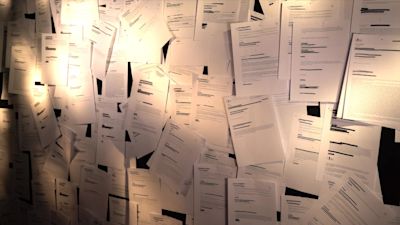

Hundreds and hundreds of parents wrote in to tell us their experiences. Some were harrowing to read. Sentences like these shot off the page...

“I have been fighting for 5 years to get a referral and some support for my child. No one will see us. No one will help us.”

“I think the only way she will get help is if she tries to kill herself then maybe they will finally help her.”

“I have been awaiting assessment for my son for over 2 years now, everytime I call I get told ‘we are sorry but we don't have funding’. "

“I know they are significantly underfunded but where do you go for help?”

These parents are trying to access specialist crisis support from the NHS. It comes under many names, depending on where you live. But it’s commonly known as CAMHS - Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

We were flooded with stories of long waiting lists for CAMHS, and in some cases rejected referrals.

The Children’s Commissioner has been too. This prompted them to start looking at what was happening. They write a report every year on the state of children’s mental health services.

In their most recent report, they said that

These latest figures are pre pandemic. Since then there’s been an explosion in demand.

The Children's Commissioner says that means the gap between children’s needs and services is likely to have grown much greater.

The pandemic has indeed turned the lives of children upside down. And the NHS says that one in six children now has a probable mental health disorder. But services were struggling before the pandemic.

The Children’s Commissioner warns that the most up to date figures cover the period up to the end of March 2020, and ‘shows a system without the necessary capacity or flexibility to respond to such seismic events in the lives of children.’

The impact on families

The families we spoke to and filmed with were all keen to stress that they have been battling for help long before the pandemic.

We spoke to one family whose child picked up a kitchen knife and threatened to kill themselves almost 2 years ago. He has only just had a referral to CAMHS accepted.

Another family whose child has daily rage attacks say they were told not to even bother trying to get on the waiting list as they were likely to be disappointed.

This all takes a huge strain on the entire family. It was heartbreaking to see the impact on parents and siblings.

We were also acutely aware that we were being allowed into people’s homes to see the most painful thing in their lives.

They did it because they wanted people to see what was happening to them and they said they wanted things to change, for them and for others.

GPs feel frustrated

It can take its toll on professionals too. It’s often the family doctor who will refer a child they believe needs specialist help to CAMHS.

GPs told us about feeling frustrated and confused if the referral is rejected and about feeling stuck in the middle when a family finds itself on a long waiting list.

Dr Nishan Wirtunga is a GP, and describes the process as 'heartbreaking'.

The more we investigated, the more we realised that it’s not just about the crisis services at the top.

Charitable organisations, schools, GPs all said the same thing: that there needs to be a bigger focus and more funding not just for CAMHS, but for early, preventive measures.

Mental health nurse, Nikki Webster, says the frustration takes its toll.

Meanwhile, mental health expert Jennifer Wyman says more preventative measures would stop children from feeling like they are 'drowning'.

The consequences of not helping a child quickly enough hit home to us when we went to speak to Marcellus Baz. He runs a boxing school and mentors many young people.

A NHSE Midlands spokesperson said:

“Staff are now treating more children and young people than ever before – the NHS has responded rapidly to the increased demand with a wide range of services available for those who need help, including through mental health support teams working with schools across the country and 24/7 freephone crisis lines for all ages, set up last summer.

“We are currently working with all health services in the Midlands with a focus this year on improving and investing in child and adolescent mental health services, as well as sharing best practice, this includes community and discharge support as well as eating disorder services.”

We repeatedly asked the Minister for Mental Health, Suicide Prevention and Patient Safety, Nadine Dorries for an interview, but she was unavailable.

In a statement she said:

“I am acutely aware of the impact the pandemic has had on the mental wellbeing of our children and young people and this government is absolutely committed to supporting them, both now and in the future.

“We know just how vital early intervention and treatment is, and we are providing an extra £2.3 billion a year to mental health services by 2023.

"This funding is going to make a real difference to young people’s lives by giving an additional 345,000 children access to NHS-funded services or school and college-based support by 2024.

“At the same time we’ve invested an additional £500 million in our cross-government Mental Health Recovery Action plan which will specifically target support to those that have been most impacted by the pandemic, including individuals with severe mental illnesses, young people, and frontline staff.”

What has been done to improve services?

In recent years there have been a number of initiatives and commitments to improving provision for children’s mental health.

In 2017 the Government published a Green Paper with plans to improve early prevention and a bigger focus on what can be done in schools.

There is now funding to train mental health leads in schools and the Government says it’s on track for 35% of schools to have Mental Health Support Teams by 2023.

These teams are supervised by NHS staff and provide a bridge into schools, focusing on mild to moderate mental health issues.

This initiative has been well received by schools, and early data suggests they are having a good impact.

But the Children’s Commissioner says she wants to see the rollout ‘rocket boosted’ and members of the Health and Social Care Select Committee, which is holding inquiry into services for children’s mental health, have pointed out that at this rate 65% of schools will still not have MHSTs by 2023.

Research funded by the National Institute for Health Research also found that ‘Some schools and colleges reported that the mental health support teams were not able to help some of their children and young people who were most in need of support.

This particularly related to children whose needs were greater than ‘mild to moderate’ (the group that the teams were designed to serve) but still not deemed serious enough to meet the referral criteria for specialist mental health services.

Schools and colleges raised concerns about this group of children and young people falling between gaps in local provision.”

The NHS wants to be able to give specialist support to every child who needs it by 2028.

The people I’ve spoken to are sceptical this will happen unless the Government moves more quickly and is more ambitious.

It matters. To children, to their families, to their teachers, their doctors. And as former Health Secretary Jeremey Hunt said, it matters to us all.

Support

If you've been affected by this story, there is support available at the following links: