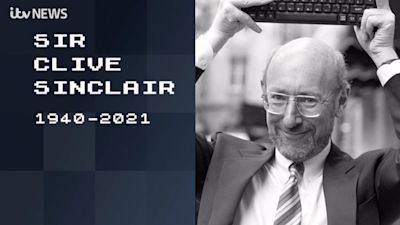

Cambridge computing pioneer Sir Clive Sinclair dies aged 81

Watch Sarah Cooper's report for ITV News Anglia

Cambridge inventor Sir Clive Sinclair, who pioneered Britain's microchip revolution, has died aged 81.

The maverick entrepreneur masterminded an incredible shrinking world of tiny computers, televisions and even cars.

But the shy guru of new technology also had remarkable plans with his vision for the future of the world - one where robots would carry out our every command.

He was born on July 30 1940 into a middle-class London background. His father was an engineer and designer of machine tools.

Sir Clive went to a succession of schools - Boxgrove Preparatory in Guildford, Highgate, Reading and St George's College, Weybridge - before quitting formal education at the age of 17.

He became a technical journalist with Practical Wireless, where he wrote specialist manuals. After four years, at the age of 22, he formed his first company, Sinclair Radionics.

He set up the company in 1962 at a house in Islington, north London, with just £25 borrowed from a friend.

The firm made small radio kits and sold them by mail order, the most well-known being a matchbox-sized product which was the smallest transistor radio in the world.

In 1967, Sir Clive moved his company to Cambridge, where a "club" of self-made young entrepreneurs with revolutionary business thinking was starting to form.

Sir Clive pioneered the pocket calculator, which earned him the title of "electronics wizard" but had tough competition from Japan and the US in the fast-moving consumer markets.

An expansion into digital watches led to trouble, but in 1976 the Labour government's National Enterprise Board (NEB) poured in capital to help him complete development of his first miniature television set.

It was launched as the world's smallest television set, having only a two-inch screen, but Sir Clive ran into trouble again with an almost £2 million loss.

By 1979, the NEB saw the future of Sinclair Radionics in the steady business of selling scientific instruments in known markets, but Sir Clive wanted the rollercoaster world of consumer electronics and left with a reported £10,000 golden handshake.

He set up his current company, Sinclair Research, at the start of the computer boom and in 1980 launched the Sinclair ZX 80 personal computer.

It astonished the world. Barely a generation before, computers cost thousands of pounds and occupied special rooms. The ZX 80 measured 9in x 7in x 2in and cost just £99.95.

Sir Clive then launched the even more powerful ZX 81 in March 1981.

It sold half a million units with the price tag cut to under £50 before the American and Japanese competition could catch up.

In April 1982 he launched the ZX Spectrum, the start of a wider and more powerful range of Sinclair computers to come.

By 1983, Sinclair had become the first company in the world to sell more than a million computers - making it a household name around the Western world.

Sir Clive also realised a radical change in television design with a new version of the Sinclair pocket television, using a unique flat screen.

He had numerous other projects on the boil, the biggest gamble being a small, highly manoeuvrable electric car.

The C5 was a low-set, one-person, battery-powered tricycle. It was a critical and commercial flop, but went on to become a cult item for collectors.

In 1983 Sir Clive bought a 200-year-old manor house near Cambridge and offered top salaries to scientific geniuses to establish his own "think tank".

He owned 95% of his company when 10% of its shares were placed in the city in 1983. The outcome then valued his personal worth at around £130 million, making him one of the country's richest men.

At the time he separated from his wife, they had three children.

He was knighted in the birthday honours in June 1983 after his many accomplishments had been praised as examples to British industry.

Sir Clive had many interests. He was chairman of British Mensa, the High IQ society, a trustee of the Cambridge Symphony Orchestra, and a marathon runner, competing in the London and New York events.

His great passion was poetry - between thinking up numerous ideas for future products and the social and economic changes he predicted would take place in Britain through the growth of new technology.

Many people who worked for him went on to form their own highly successful companies - a process which Sir Clive welcomed.

His vision of the future was that industry in Britain would be based around small, innovative groups of people - not large factories - producing "products of the mind".

It was a vision Sir Clive sought to establish, with one of his ultimate products being a domestic robot which would carry out household duties on command.