Month-old babies among Philippines' modern slavery victims as lockdown fuels exploitation pandemic

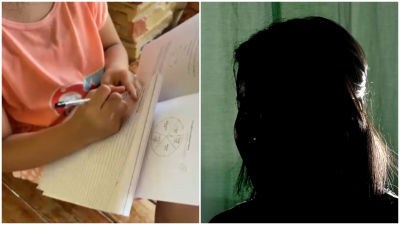

A report by ITV News Correspondent Lucy Watson shows mothers being arrested for exposing their children to paedophiles

Warning - this article contains distressing images and themes

The issue of modern slavery in all its forms has got under my skin over the past 18 months.

The more I learn, the more I feel I need to know. The more I hear, the more horrified I become. It is not a subject you become desensitised to.

In February this year, a conversation led me to start looking into child sexual exploitation online in the Philippines.

I found out that parents were putting their own children on the web to be abused by paedophiles from abroad, and the majority of ‘clients’ were coming from the UK, US, Australia and western Europe.

It is an ongoing problem but it got worse during lockdown. More people at home and on the internet created a greater customer base, and more children trapped in their houses made them increasingly vulnerable. The figures surrounding the issue are breathtaking.

According to research done by the International Justice Mission, the Philippines is the largest known source of online sexual exploitation cases (OSEC) in the world, and 83% of cases of child sexual exploitation on the internet in the country are carried out by family members.

Staggeringly, on 25 May, 2020, the Philippines Department of Justice confirmed a 264% increase in OSEC reports since the beginning of the pandemic. More dreadful than those statistics were the police rescue videos I was sent, showing the type of children affected by these crimes.

One little girl being lifted out of a moses basket by police officers at a home in the capital Manila was just three-months-old. Her mother was arrested on suspicion of sexually exploiting all seven of her children on the internet.

We also heard from victim, Cassie (not her real name), who said that “every day, morning, afternoon, evening, there is a lot of customers."

Cassie was 12 when she was first sexually abused online. A family friend had convinced her parents to let her live with him miles away from her home, on the promise of a better education. Instead, she was put on the internet every single day before and after school for “customers”.

Offenders would tell her trafficker what they wanted to see and he would do it to her, while the paedophile watched the abuse from thousands of miles away. Five others who lived with her suffered in the same way.

"There was a one-year-old, six-year-old and five-year-old, 21-year-old, 16-year-old and me," she says.

"The guy will ask my recruiter to touch a part of my body. I can't cry because when he sees me crying he is going to slap me."

In Luzon, north of Manila, police showed us footage of another mother being arrested. She was wailing to see her children even as evidence was gathered from her various mobile phones."

The room next to the kitchen, where police were speaking to her, was a playroom where she was suspected of exploiting seven children online. Four of them were her own. The reasons why a parent could do such a thing are unfathomable, but the executive director for the International Justice Mission’s Centre to End the Online Sexual Exploitation of Children tried to explain it to me.

His name is John Tanagho and his organisation works to rescue vulnerable children in the Philippines, create public awareness campaigns to encourage community reporting of the crime, and work with police globally to help prevent it.

He said: "The fact that the offender does not physically touch the child, but is on a screen miles away, makes the relatives feel that it isn’t actual abuse.

"Also, culturally in the Philippines, the family and the prosperity of the family are the main priorities, so everyone must pull their weight, and the sex industry is lucrative. But most importantly, people are simply getting away with it."

“They're not afraid of getting caught because they know that it's not being detected by the platforms on which it's happening," he added.

He told me paedophiles and traffickers seek each other out on social media, exchange numbers and then make arrangements for the abuse through text message.

Money is then passed through bank accounts via money transfer agencies. The first conversation, the money exchange and the actual abuse can all be done on a mobile phone.

'This is a pandemic': John Tanagho breaks down the dangers faced by exploited children

“The sex offender says I want to see a six-year-old girl sexually abused by an adult. The trafficker says I can do that but I'm going to charge you," Mr Tanagho said.

"The offender sitting in the UK wires the money and then they have a video call and that's when the child is sexually abused. This is a pandemic."

Much of this abuse is often ‘live’ too. According to Europol’s Serious and Organised Crime Threat Assessment 2021, live-streamed child sexual abuse has “intensified” in the past year, and the problem with ‘live’ exploitation is that once it’s happened, it’s gone, leaving no trace.

Similarly, in monitoring darknet sites, Europol reported an increase in the sharing of child sexual abuse material captured through webcams early in the pandemic (from March to May 2020).

This means that offenders are screen-grabbing images and recording videos from live streams, then sharing the images on the darkweb in various forums.

Preventing child exploitation online is of course the job of law enforcement around the world, but it is also what companies like the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), working alongside the National Crime Agency, are trying to help put a stop to.

IWF is based in Cambridge, and Chris Hughes oversees a team of analysts there who see harrowing images every day.

"The scale of the problem, you have to see it to believe it. There are so many children that are being abused on a daily basis. There's no getting away from it," he said.

"Some of the images are considerably challenging, particularly those images that involve very young, if not month-old, babies can be particularly distressing for the team... but once we've got clearance we can have content removed as quickly as within five minutes."

Last year, they removed more than 150,000 web pages and millions of images, yet the organisation is funded by the very tech firms that often host the abuse.

IWF’s chief executive Susie Hargreaves told me it’s not just the tech firms we are familiar with - the household names - that we should point the finger at.

'All of us can do more... you just see children robbed of their childhood': Susie Hargreaves, IWF chief executive, says changes can't be made without cooperation of tech companies

“They are the ones trying to be responsible and bring in measures to crack down on the problem," Ms Hargreaves said.

"It is the companies that we’ve never heard of that often harbour the abuse, so for that reason there needs to be collective effort and blanket regulation.

"The tech companies can do more, and we can do more. All of us can do more. I think, none of us are going to sit here and be complacent until we've removed all the child sexual abuse there is online.

"But this is also a problem you can't solve without the tech companies. We need to throw everything we can at this problem. You just see children just robbed of their childhood."

Google and Facebook declined to give ITV News an interview regarding our findings in the Philippines, but in a broader context Google did say: “We’ve been committed to fighting online child sexual exploitation and abuse both on our platforms and in the broader online ecosystem since our earliest days.

"We’ve invested heavily in the teams, technology, and resources to deter, remove, and report this kind of content, and to help other companies do so – and we publish the results of our efforts in our transparency report.

"This issue cannot be solved by any one company, that’s why we’re committed to tackling it with industry and partners like the Internet Watch Foundation who are dedicated to protecting children.”

Many parts of the Philippines are still in tight lockdown and the rates of vaccination are slow, leaving many children still much at risk.

The hope is that the Online Safety Bill will, in the future, place a duty of care on online platforms to detect and report illegal content created or shared by users, including child sexual abuse materials.

This will be a significant step in protecting vulnerable children, as it will provide crucial information to law enforcement in the UK and internationally, helping them quickly identify and safeguard victims, investigate offenders, and reduce the likelihood of abuse occurring through preventative measures.

What’s more, organisations who deal with this problem first-hand want the Bill to incentivise platforms to create early detection tools, so they can pick up illegal content - like the livestreamed abuse of children - and above all, they want online platforms to be more accountable.

This is surely essential when protecting the innocence of children.