Researchers tap into paralysed man's brain and display his speech on a screen in a world first

ITV News Science Editor Tom Clarke reports on the breakthrough as brain waves of a paralysed man turn into sentences

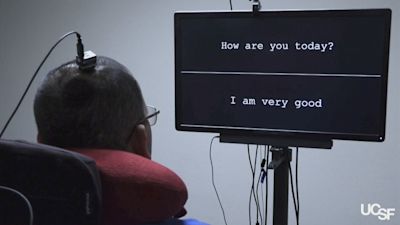

For the first time researchers have used brain waves of a paralysed man who is unable to speak and have turned them into sentences on a computer screen.

The study, which will require more years of research, marks a monumental step in allowing more natural communication for people who can't talk due to illness or injury.

Dr Edward Chang, a neurosurgeon at University of California who led the work, said: “Most of us take for granted how easily we communicate through speech.

"It’s exciting to think we’re at the very beginning of a new chapter, a new field” to ease the devastation of patients who lost that ability."

Those who cannot speak or write due to paralysis currently have limited ways of communicating.

The man in the experiment, who has not been identified for privacy reasons, usually uses a pointer attached to a hat that lets him move his head to touch words or letters on a screen.

Other devices can pick up eye movements, but it can be a frustrating and slow substitution for speech.

How was it done?

Dr Chang and his team built developed a “speech neuroprosthetic” which decodes brain waves that normally control the vocal tract, the tiny muscle movements of the lips, jaw tongue and larynx that form each consonant and vowel.

The man that volunteered to take part in the research is in his late 30s. He suffered a brain-stem stroke 15 years ago that caused paralysis and he has been unable to speak ever since.

The researchers implanted electrodes on the surface of the man’s brain, over the area that controls speech.

A computer analysed the patterns when he attempted to say common words such as “water” or “good,” eventually becoming able to differentiate between 50 words that could generate more than 1,000 sentences.

Prompted with such questions as “How are you today?” or “Are you thirsty” the device eventually enabled the man to answer “I am very good” or “No I am not thirsty."

It takes about three to four seconds for the word to appear on the screen after the man tries to say it, said lead author David Moses, an engineer in Dr. Chang’s lab.

In an accompanying editorial, Harvard neurologists Leigh Hochberg and Sydney Cash called the work a “pioneering demonstration.”

They suggested improvements but said if the technology pans out it eventually could help people with injuries, strokes or illnesses like Lou Gehrig’s disease whose “brains prepare messages for delivery but those messages are trapped.”

Next steps include ways to improve the device’s speed, accuracy and vocabulary size and maybe one day allow a computer-generated voice rather than text on a screen.