Covid: Behind the scenes in the lab investigating whether coronavirus vaccines work against variants

Tom Clarke

Former Science Editor

While the government is grappling with the vaccine rollout and new, more transmissible variants of Covid-19, what everyone wants to know is if we will be protected against the more infectious strains after our jabs.

For a first-hand look into the work going into these investigations, ITV News and Science Editor Tom Clarke were given exclusive access to a laboratory in Glasgow - where scientists are trying to determine how successful our treatments and vaccines are against the new Covid iterations.

It takes steady hands to work with live coronavirus. And to handle the more infectious variant that’s become the UK’s dominant strain — steady nerves as well.

But here, in an air-locked lab at the MRC Centre for Virus Research at the University of Glasgow, Dr Wilhelm Furnon is calmly using a pipette to take samples of the virus extracted from Covid patients and mixing them with a soup of human cells in a flask - deliberately infecting them.

Why?

To answer some of the most urgent questions of the Covid pandemic right now: how come new variants of the virus are more infectious? And will our vaccines and other treatments work against them?

One way of finding out is to just sit and wait and see whether the vaccines we’re rolling out work. But it could take months until enough people are vaccinated and later infected to see that impact.

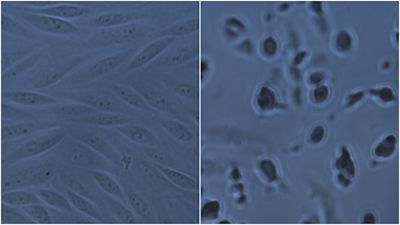

What's the difference between healthy cells and those infected with Covid?

And by then it would be too late to do anything about it, which is why scientists like Dr Furnon are so busy.

It’s around one month since clear evidence started appearing of more infectious new variants of Covid.

But teasing apart the mechanism for how they’re doing it and what that means for our immunity to them is a laborious process.

The variants have slightly different combinations of genetic mutations and right now researchers are largely guessing what those mutations might actually do.

One approach is the one we’re witnessing.

Taking virus from patients and infecting human cells with it – and then trying to protect those cells from further infection using antibodies made against the vaccines.

If the antibodies do that job, it’s reasonable to assume they will outside the lab too.

Early experiments are showing, thankfully, that the antibodies we produce due to the vaccine do work, albeit with reduced potency, against the UK variant.

Centre Professor Massimo Palmarini on the importance of understanding new variants so that decisions can be made to contain the spread

But there is more concern about the new infectious variants circulating in South Africa and Brazil.

A study from South Africa published on Thursday suggests this virus could “escape” the immune system of people previously infected (and therefore possibly the same for people vaccinated).

Emma Thompson, a virologist at the Centre for Virus Research and an infectious disease consultant in the NHS, thinks the emerging evidence on these other new variants makes it “almost inevitable” that we will need to make new vaccines against the constantly evolving virus for use in the not-too-distant future.

But what should these vaccines look like? It’s already a question the lab studies are trying to answer.

The team in Glasgow is part of a new research collaboration of 10 institutions across the UK called G2P working to explain which genetic mutations in the virus are important, and why.

One approach to doing that requires a more clever, but slightly slower approach than infecting cells with Covid-19 virus from patients.

Scientists in the lab deliberately infect cells with Covid

Instead, researchers are creating their own synthetic Covid viruses by reverse engineering their genetic material.

That allows them to select which genetic mutations of interest their viruses express.

They can then see what effect they have in isolation, or in varying combinations — like detectives eliminating suspects, they can hone in on the ones that give these viruses their more infectious edge, and also the ones that need to be included in any new vaccines we need to make against Covid.

It could be several more weeks before these experiments yield results.

But anything that gives an early indication of the new dangers rapidly evolving Covid variants could present will make all the difference in this fast-moving pandemic.